When I was in the fifth grade I told my parents I was going to be a historian. My favorite period was World War II, because when I was in grammar school the original first person POV recounts of war heroes or of being in occupied France or working in the resistance were coming out. I remember reading the harrowing story of Douglas Bader , how he lost his legs in a training accident but it allowed him to turn a one eighty faster and not black out because his blood

didn’t go clear to his feet. He was the whole reason I bought a Triumph Spitfire in the late 70s. But no, I did not have the intellectual rigor or the ambition toward high grades, I simply wanted to know history–all of it. When I was in college those were the only programs I was interested in, the history ones and anything ancillary to history, like urban geography–now that was a blast. But, I digress.

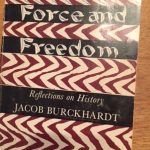

One of the requirements of a BA in history at CalState Northridge was to participate in a seminar class and write a thesis. Because of reading so much history up to this point I was less interested in a particular period than I was in the idea of history, the theory of writing history, what it meant, not only to me, but to anyone else. How they used it. How it came to be identified. Was it truly the victor who wrote the history? I was stymied until my professor–who later hated my paper–recommended Jacob Christoph Burckhardt and I started doing some research. I remember my professor talking about the fact that Burckhardt was the one who named the period Renaissance. How cool!

As I recall, Burckhardt was a terrible historian, but what fascinated me was his writing on history. He was distinctly Swiss, distinctly European, at a time when conservative could mean

culturally and not politically conservative. As I look back through FORCE AND FREEDOM , Reflections on History by Jacob Burckhardt, I see my notes and what it was that drew me into his writing. Though Protestant, his view of Roman Catholicism was that ‘Rome at least [able to] set other goals than those of power and comfort, steadily opposed the increasingly totalitarian claims of national states and maintained the intelligently realistic view of human nature which Burckhardt considered essential to political responsibility.’ He felt that liberals wanted people to think all things were possible and most people think possible means the material. Liberalism meant no sense of responsibility, no respect, no inner acceptance of the readiness to renounce for the good of the whole. He felt that democratic programs would eventually fall to ruthless military authority–that democracy eventually offered an over-developed state machine that would seize and exploit the state and thus the people, this was despotism built brick by brick, a paradigm exemplified by the straight line from the French Revolution to the Napoleonic Empire. Ah, history. How you look to repeat and repeat and repeat. Again, I digress.

Burckhardt felt that ‘historical consciousness is what distinguishes the civilized man from he barbarian, and that the race has a sacred duty to preserve the memory of it’s greatest trials and triumphs.’

Until I returned to Burckhardt’s book lately, life had run by and through me for so long I forgot why my love of history. It reminded me of what Linda Sue Park said during a non-fiction session at SCBWI LA; she was only interested in truth’, and that each of us writing narrative nonfiction need to ‘be honest with self’ and ‘passionate for the topic.’

As I document my journey to, hopefully, publication of the narrative nonfiction I have optimistically entitled SACRED TRUST, The Congo from Leopold II to Dag Hammarskjöld I hope the best of it is in the nature of Burckhardt’s ‘sacred duty to preserve the memory of it’s greatest trials and triumphs.